No Echo Read online

Page 7

He pointed at the sign on the door in the glass wall dividing off the corridor.

“Yes. Take a seat.”

There was barely room for him. One of the longer walls was covered from floor to ceiling with packed bookshelves. On the floor beside the doorway sat an enormous stack of books that the office was too small to house. An incredible quantity of papers, stashed among pens and cups full of pencils, lay on the broad desk under the window. A grubby plush Moominpappa soft toy perched on the far edge of the table, the brim of his top-hat torn, and stared vacantly at a colorful Gustav Klimt poster. A bulletin board plastered with cartoons, a couple of photographs, and three newspaper cuttings hung crookedly above Billy T.’s head. Idun Franck removed a pair of gold-rimmed glasses and polished them with her sweater sleeve.

“How can I help you?”

“Brede Ziegler.”

Feeling claustrophobic, Billy T. tried to reach the handle of the door he had just closed behind him.

“I can open the window,” Idun Franck said with a smile. “It gets a bit stuffy in here.”

A puff of cold, exhaust-laden air forced its way into the room.

“Not much of an improvement, I’m afraid.”

Nevertheless she left the window open.

“I did realize it would be about Brede Ziegler,” she said pointedly as she put her glasses on again.

“Yep. I’ve learned that you’re working on a book. About Ziegler, I mean.”

“Do you usually interview witnesses at their place of work? I had anticipated some kind of summons. I thought that was how you normally went about these things.”

The woman did not seem hostile, despite her appropriate reprimand. Billy T. scrutinized her while scratching his thigh. She must be around fifty. Although she could not be described as fat, she was certainly well built. Her breasts strained behind the green sweater: the stitches were stretched, revealing her black underwear. She peered at him over her glasses, as if she did not quite know what to make of him.

“You’re right,” Billy T. said, grinning. “It is slightly irregular. But I was in the neighborhood and thought I might as well pop in and see if you were here. You don’t need to talk to me at all. In any case, you will be called for interview later. For a formal interview, I mean. And if you—”

He started to rise from his chair.

“Stay seated.”

Her voice reminded him of his mother’s. He did not know whether he liked that or not. He sat down again.

“Officer,” she began.

“Chief Inspector, in fact, though that’s not so important.”

“I didn’t catch your surname.”

“That’s not so important, either. Billy T. is plenty. Is it true that you’re writing a book about Ziegler?”

Idun Franck removed the elastic band holding her hair back in a ponytail. Only now did Billy T. notice that she had thick streaks of gray in her ash-blond hair. However, her face looked younger with her hair loose; her cheekbones no longer seemed so schoolteacherly severe, beneath her unusually large eyes.

“Well,” she said, her mouth contracting into what might be some sort of smile.

“Well?”

“I wasn’t actually writing a book about Brede Ziegler. I’m an editor, not a writer or an author.”

“But—”

Billy T. produced a newspaper cutting from his inside pocket and spread it over his knee.

“This was in Aftenposten three weeks ago or—”

“That’s right. We had planned to publish a culinary biography. A kind of odyssey through Ziegler’s life and work, if you like. With recipes and anecdotes, his life story, and pictures. Unusually, I was to do the writing, but the plan was that this should be a sort of autobiography. A hybrid, so to speak. In several places the text would be written in the first person. Is this important?”

Again the corner of her mouth tugged into what might be construed as a smile. Her face took on a slightly mocking aspect, and Billy T. felt his armpits sweat. He pulled off his jacket, though he had no idea what to do with it.

“Did you already know Ziegler?” he asked, dropping the jacket on the floor.

“No. Not before I met him in connection with this project.”

“But you now know him well, isn’t that so? I mean, how far had you got with this … cookery book?”

Idun Franck suddenly got to her feet and used both hands to brush her tweed skirt.

“I should have offered you coffee, of course. Sorry. Black?”

She grabbed her own mug and disappeared without waiting for an answer. The phone began to ring. Billy T. stared at the apparatus. The sound was unusually discordant: an old-fashioned, piercing ring that made him rise to pick up the receiver. As he hesitated momentarily, it fell silent.

“Are you looking for something?” he heard at his back and wheeled round abruptly.

Idun Franck had returned with two cups of coffee and was staring at him with an expression he interpreted as somewhere between irritation and curiosity.

“The phone,” he said, pointing. “The ring was so damn loud. I thought I should answer it, but then it stopped. Bloody awful noise.”

Idun Franck’s laughter was unexpectedly deep and husky. She snaked her way past Billy T., handed him a cup, and fished out a cigarette from a pack of Barclay extra-mild in a drawer.

“Does it bother you?” she asked, lighting the cigarette.

“No, it’s fine.”

“Where were we?”

Once again she stared at him over her glasses. For the first time it struck Billy T. that he found this somewhat overweight fifty-year-old woman attractive. She made him feel hesitant and awkward. He had to pull himself together to avoid his eyes lingering on her bust.

“How well did you know the man?” he repeated, shuffling his feet. “How far had you reached in the work on this book?”

“It’s actually difficult to say. People have a tendency to think that a book project is like … a fifty-kilometer ski race, for example.”

She took a long drag, betraying that she was used to far stronger cigarettes.

“It’s surprising how many people believe that a book is completed by placing one stone on top of another. It’s not normally like that. The process is more … organic, you might almost say. Unsystematic. So I can’t …”

Billy T. again felt the gaze above her glasses that forced his eyes to stray to the Moominpappa, which had now toppled on to its back and was staring at the ceiling.

“… say how far we had reached.”

“Okay, then,” Billy T. said, clearing his throat. “That’s fine. But can you tell me whether, through the work you’ve done to date, you’ve learned anything about who … or what – whether he had difficulties with anyone? Conflicts above and beyond the everyday?”

Idun Franck took a gulp of coffee and a last puff of her cigarette, before stubbing it out and dropping it into a Farris bottle. She leaned across the desk and closed the window. Afterwards she remained seated with her eyes half-closed, as if thinking through a lengthy exposition.

“Billy T.,” she said quizzically.

He nodded.

“Chief Inspector Billy T.,” she said long-windedly. “You are intruding on an extremely problematic area now. I am actually an editor. As you almost certainly know, that gives me certain editorial responsibilities. I can’t say just anything to just anyone. You are asking me about things that I might possibly have learned from a source I have spoken to, in connection with work on an as-yet-unpublished book.”

“So what?”

Billy T. opened out his arms expressively, narrowly missing a mind-your-own-business potted plant on an adjacent sideboard.

“Confidentiality of sources,” Idun Franck said, smiling. “Publisher’s ethics.”

“Confidentiality!”

Billy T.’s voice rose to a falsetto.

“The guy’s dead, and you’re not bloody working for a national newspaper! Of all the preposterous

things I’ve heard – and believe me, there’s been a whole fucking lot of those over the years – you’ve got the nerve to tell me you plead confidentiality for your sources, in connection with a cookery book! What the hell kind of book is it, then? Full of secret recipes or what?”

Idun Franck used her coffee cup to heat her hands: broad hands with short nails. On her left hand she wore a large ring of Viking design. She tapped it against the cup in a regular nerve-racking beat.

“If you reflect on it, I think you’ll understand the problem. I’ve initiated a collaboration with a man who is going to tell me about his life, so that I can obtain enough material to publish a book. What would be printed of what he has told me was to be decided much later in the process. Everyone we obtain material from, whether it is authors or anyone else, is assured that what gets published will only go to print with their full agreement. I’ll permit myself to refer you to both the Criminal Procedure Act, section 125, and to the European Convention on Human Rights. Article ten, if I’m not entirely mistaken. If I gave you information now, under cover of the fact that Brede Ziegler is hardly in a position to protest …” She stopped and held her breath for a moment or two before continuing: “… then none of my authors would be able to trust me in future. It’s as simple as that. I had a purely professional relationship with Ziegler. Talk instead to those who knew him personally.”

Billy T. thought he detected a touch of vulnerability about this person who had sat with her back turned and let herself feel alarmed at his approach.

“How wrong can you be?” he said, retrieving his jacket. “You want to play hardball. Okay then. We too have lawyers to deal with that sort of thing.”

There was nothing more to be gained here. As he headed for the door, the phone rang again. The window opened by itself, and a strong blast of air lifted four sheets of paper from the desk. All of a sudden Billy T. was aware of a whiff of perfume from Idun Franck, a fragrance he had not encountered for a long number of years. It made him dizzy. When he irritably raised his hand in some kind of farewell gesture to the publishing editor as she spoke on the phone, he narrowly avoided colliding with a young man. Billy T. thought he recognized the boy.

“Authors just keep getting younger and younger,” he muttered, pulling on his jacket as he strode off.

12

Thomas needed to pee. If he did not think about it too much, he might manage to reach all the way home before he came to grief. Even though he was seven and a half, he sometimes wet his pants. Yesterday he had met a man with a blue nose. The man was terribly old and his awful stink extended as far as the electricity substation where Eirik, Lars, and Thomas were doubled-up with laughter, yelling and jeering from their hiding place as they stared at his huge bright-blue nose. When the man had crossed Suhms gate at the gas station, Thomas had been left standing with a wet patch on the front of his trousers and a yellow puddle at his feet. Running home with the hilarity of his pals at his back, he nearly got knocked down by a car.

Now he stood on tiptoe at the gate with his legs crossed. His mum preferred him to wear the key around his neck. Dad had given him some sort of janitor’s gizmo at Christmas: a metal key ring that could be fastened to his belt. Thomas had to stand on tiptoe to make the key’s cord long enough. At last the key slipped in and the gate slid open. Thomas rushed into the entrance.

“Somersaults, sandcastles, sardines.”

That usually helped. Long strings of words with difficult S-words. He had posted a list in his room, and constantly added new and increasingly difficult words that he could learn by heart.

He came to a sudden stop before he reached the front door. The witch was on the prowl. Thomas Gråfjell Berntsen never walked past Tussi Gruer Helmersen of his own free will. Mrs. Helmersen on the first floor was the only person in the whole world of whom Thomas was really scared. Once she had bumped into him on the stairs and made him fall. Not that he hurt himself at all badly, but since then he had suffered nightmares about her yellow eyes. If she came upon him unawares – something that happened increasingly infrequently – she was in the habit of pinching him hard on the cheek in some odd kind of greeting.

Thomas could not hold out any longer. He stood behind the garbage bins, not daring to move a muscle, with tears welling up in his eyes.

Mrs. Helmersen was wearing her dressing gown, even though the weather was quite chilly. That probably meant she was heading straight back up again. Thomas closed his eyes and sobbed through gritted teeth: “Go away. Go away!”

But Mrs. Helmersen stood still, with only her head moving, as if she were looking for something.

“Pussy! Here, puuuuusssy! Come on, pussy-cat!”

Mrs. Helmersen did not have a cat. She hated cats. Thomas knew she had complained to the management. About Helmer, a ginger tomcat that Grandma had given Thomas for Christmas two years ago. Actually he had wanted a dog, but dogs were not allowed.

“Clever puss,” he heard Mrs. Helmersen say. “Drink it all up, that’s right.”

As Thomas held his breath, he peeped out from behind the garbage bin. Mrs. Helmersen was crouching over Helmer, who was lapping milk from a saucer.

Finally she moved away. She really did not seem human and instead reminded him of some kind of robot, her movements were so stiff and frightening. Thomas’s teeth were chattering, but he was reluctant to creep from his hiding place until he was certain that Mrs. Helmersen had returned all the way up to her apartment.

Eventually he felt reasonably safe. His trousers chafed on his crotch as he sneaked up on Helmer, who was still licking a white saucer decorated with tiny sprigs of flowers. He picked up the cat.

“Did Mrs. Helmersen give you some food?”

The soft cat’s ear against his mouth made him burst into tears. When he arrived at his own apartment and managed to strip off his clothes, he was still freezing cold. He knew he ought to wash, but wanted to wait for his mum. He crept into bed, pulling the quilt over himself and Helmer. The cat was whimpering softly. Thomas fell asleep.

When he woke just before five, when he heard that his mum had come home, Helmer was dead.

13

Only afterwards did he notice the warning on the package. He had taken two Paracet tablets an hour ago. Now he had swallowed down another two and the bitter taste burned his throat. He read the warning yet again, shaking his head.

“If only this damn tooth would let up.”

It was not going to let up. Lately it had throbbed whenever he drank or ate anything either above or below body temperature. This evening the toothache had taken complete hold. Billy T. did not want to visit the dentist. Admittedly, the tooth was a goner. The dentist would take one look at the damage and suggest a crown. Three thousand four hundred kroner for a single crown. Out of the question. To put it mildly, Billy T. could not afford it. Jenny would need a pushchair soon. Four child-support payments in addition to Jenny made him sick every time his paycheck arrived. The pay rise that had accompanied his temporary appointment as chief inspector in charge vanished in one huge gulp.

He needed money. As far back as he could remember, he had been short of cash.

The toothache sneaked up the left side of his face and ended as a shooting pain somewhere deep inside his head. He wrung out a dirty cloth and pressed it against his eyes. The faint reek of baby poo made him snatch it off again.

“Shit. Shit!”

He snarled at his reflection in the mirror. The fluorescent light made him look more pallid than he actually was, and he stood there rubbing his temples as he struggled to squint away the bags under his eyes. It was past midnight and he really ought to grab some shut-eye while Jenny permitted it.

Warily, he opened the bedroom door.

Jenny was lying on her back in the cot with her arms outstretched, the quilt in a tangle at her feet. She resembled a sunbather in blue pajamas. Billy T. carefully covered her with the quilt and pushed the grubby yellow rabbit into its usual place in one corner.

He felt

Tone-Marit’s warmth on his back when he lay down gingerly in the double bed. The toothache did not ease off. Instead, it grew worse.

Even though he had already sired four children, the two girls in the bedroom were his first real family. Since he had left home, anyway. At this very moment he would prefer to be alone, however. Then he would have flicked on all the lights, drunk himself to semi-oblivion from the cognac bottle that remained untouched after a business trip to Kiel two years earlier, turned Il Trittico to full volume, and waited for the pain to subside.

He wanted to be alone.

Life had been uncomplicated as a young guy and weekend dad. After a bit of early fuss with the youngest child’s mother, the arrangement had gone well. He did not interfere in how the boys fared with their four different mothers. For their part, they involved themselves only minimally in how the boys got on at his house. As long as his sons seemed congenial and healthy, he found no reason to meddle with a setup that worked. Now and again the boys sulked a little because he did not attend end-of-term functions and that sort of thing, but eventually they had grown used to it all the same. If they had football matches or other activities while staying at their father’s, then naturally he accompanied them. When all was said and done, he was having a great time.

This was something altogether different.

Jenny had not slept through one whole night since the day she was born. She bawled and screamed and demanded to be fed. Before her hunger was assuaged, the last feed was running out the other end. The apartment was too cramped to escape it. A few times Billy T. had spent the night with friends in order to get the peace he craved, but then he mostly lay awake thinking about Tone-Marit having to cope with it all on her own.

The apartment was quite simply too small, but they could not afford to do anything about it.

The bedroom was chilly and he pulled the quilt up to his chin. His feet protruded from the bottom and he curled up. Jenny made gurgling noises, and like an echo, he heard a whimper from Tone-Marit.

A Grave for Two

A Grave for Two Dead Joker

Dead Joker Death of the Demon: A Hanne Wilhelmsen Novel

Death of the Demon: A Hanne Wilhelmsen Novel Punishment aka What Is Mine

Punishment aka What Is Mine Beyond the Truth

Beyond the Truth Death in Oslo

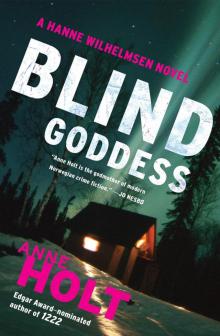

Death in Oslo The Blind Goddess

The Blind Goddess What Never Happens

What Never Happens 1222

1222 In Dust and Ashes

In Dust and Ashes Odd Numbers

Odd Numbers What is Mine

What is Mine What Dark Clouds Hide

What Dark Clouds Hide Blessed Are Those Who Thirst

Blessed Are Those Who Thirst Fear Not

Fear Not No Echo

No Echo Hanne Wilhelmsen - 01 - The Blind Goddess

Hanne Wilhelmsen - 01 - The Blind Goddess