The Blind Goddess Read online

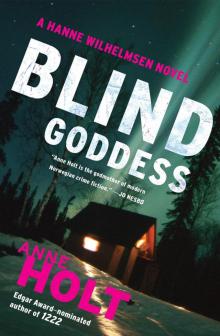

The Blind Goddess

ANNE HOLT, acclaimed author of the Hanne Wilhelmsen mysteries, has worked as a journalist and news anchor and spent two years working for the Oslo Police Department before founding her own law firm and serving as Norway’s minister of justice in 1996–97. She lives in Oslo with her family.

ALSO BY ANNE HOLT

THE JOHANNE VIK SERIES:

PUNISHMENT

THE FINAL MURDER

DEATH IN OSLO

FEAR NOT

THE HANNE WILHELMSEN SERIES:

THE BLIND GODDESS

BLESSED ARE THOSE THAT THIRST

DEATH OF THE DEMON

THE LION’S MOUTH

DEAD JOKER

WITHOUT ECHO

THE TRUTH BEYOND

1222

First published in the United States in 2012 by Scribner, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc., New York.

Published in trade paperback in 2012 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Originally published in 1993 in Norwegian as Blind gudinne

Copyright © Anne Holt, 1993

English language translation copyright © Tom Geddes, 2012

The moral right of Anne Holt to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 0 85789 705 3

E-book ISBN: 978 0 85789 232 4

Printed in Great Britain [printer fills in their details here].

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

The Blind Goddess

Contents

PROLOGUE

MONDAY 28 SEPTEMBER, AND EARLIER

TUESDAY 29 SEPTEMBER

THURSDAY 1 OCTOBER

FRIDAY 2 OCTOBER

MONDAY 5 OCTOBER

WEDNESDAY 7 OCTOBER

SUNDAY 11 OCTOBER

MONDAY 12 OCTOBER

TUESDAY 13 OCTOBER

THURSDAY 15 OCTOBER

FRIDAY 16 OCTOBER

MONDAY 19 OCTOBER

FRIDAY 23 OCTOBER

MONDAY 26 OCTOBER

THURSDAY 29 OCTOBER

TUESDAY 3 NOVEMBER

FRIDAY 6 NOVEMBER

SATURDAY 7 NOVEMBER

MONDAY 9 NOVEMBER

TUESDAY 10 NOVEMBER

WEDNESDAY 11 NOVEMBER

THURSDAY 12 NOVEMBER

FRIDAY 13 NOVEMBER

THURSDAY 19 NOVEMBER

FRIDAY 20 NOVEMBER

SATURDAY 21 NOVEMBER

MONDAY 23 NOVEMBER

TUESDAY 24 NOVEMBER

WEDNESDAY 25 NOVEMBER

FRIDAY 27 NOVEMBER

SATURDAY 28 NOVEMBER

SUNDAY 29 NOVEMBER

MONDAY 30 NOVEMBER

TUESDAY 1 DECEMBER

TUESDAY 8 DECEMBER

THURSDAY 10 DECEMBER

MONDAY 14 DECEMBER

The man was dead. Conclusively, beyond all reasonable doubt. She could tell instantly. Afterwards she couldn’t really explain her absolute certainty. Maybe it was the way he was lying, his face hidden by the rotting leaves, a dog turd right by his ear. No drunk with any self-respect lies down next to a dog turd.

She rolled him over carefully. His entire face was missing. It was impossible to recognise anything of what must once have been a person with an individual identity. The chest was a man’s, with three holes in it.

She had to turn away and retch violently, bringing up nothing but a bitter taste in her mouth and painful cramps in her stomach, letting the corpse fall forward again. She realised too late that she had moved it just enough for the head to land in the excrement, which was now spread all over the drenched dark-blond hair. That was the sight that finally made her throw up, spattering him with the tomato-coloured contents of her stomach. It seemed almost like a derisive gesture of the living towards the dead. The peas from her dinner weren’t yet digested, and they lay there like toxic-green full stops over the dead man’s back.

Karen Borg started running. She called her dog, and put it on the lead she always carried mostly for the sake of appearances. The dog scampered excitedly alongside her until it realised that its mistress was sobbing and gasping, and then it decided to contribute its own anxious whining and whimpering to a chorus of lamentation.

They ran and ran and ran.

MONDAY 28 SEPTEMBER, AND EARLIER

Police headquarters in Oslo, Grønlandsleiret, number 44. An address with no historical resonance; not like 19 Møllergata, the old police headquarters, and very different from Victoria Terrasse, with its grand government buildings. Number 44 Grønlandsleiret had a dreary ring to it, grey and modern, with a hint of public service incompetence and internal wranglings. A huge and slightly curved building, as if the winds had been too strong to withstand, it stood framed by a house of God on one side and a prison on the other, with an area of demolished housing on Enerhaugen at the rear, and only a broad expanse of grass fronting it as protection against the city’s most polluted and trafficky streets. The entrance was cheerless and forbidding, rather small in proportion to the two-hundred-metre length of the façade, squashed in obliquely, almost concealed, as if to make approach difficult, and escape impossible.

At half past nine on Monday morning Karen Borg, a lawyer, came walking up the incline of the paved path to this doorway. The distance was just far enough to make your clothes feel clammy. She was sure the hill must have been constructed deliberately so that everyone would enter Oslo police headquarters in a slight sweat.

She pushed against the heavy metal doors and went into the foyer. If she’d had more time, she’d have noticed the invisible barrier across the floor. Norwegians bound for foreign shores were queueing for their red passports on the sunny side of the enormous room. On the north side, packed in beneath the gallery, were the dark-skinned people, apprehensive, hands damp with perspiration after hours of waiting to be told their fate in the Police Immigration Department.

But Karen Borg was late. She cast a glance up to the gallery round the walls: blue doors and linoleum floor on one side, and yellow on the other, southern, side. On the west side two tunnel-like corridors in red and green disappeared into nothingness. The atrium extended seven floors in height. She would observe later how wasteful the design was: the offices themselves were tiny. When she was more familiar with the building she would discover that the important facilities were on the sixth floor: the commissioner’s office and the canteen. And above that, as invisible from the foyer as the Lord in His heaven, was the Special Branch.

“Like a kindergarten,” Karen Borg thought as she became aware of the colour coding. “It’s to make sure everyone finds their way to the right place.”

She was heading for the second floor, blue zone. The three lifts had conspired simultaneously to make her walk up the stairs. Having watched the floor indicators flash up and down for nearly five minutes without illuminating “Ground,” she had allo

wed herself to be persuaded.

She had the four-figure room number jotted on a slip of paper. The office was easy to find. The blue door was covered in paste marks where attempts had been made to remove things, but Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck had stubbornly resisted and were grinning at her with only half their faces and no legs. It would have looked better if they’d been left alone. Karen Borg knocked. A voice responded and she went in.

Håkon Sand didn’t appear to be in a good mood. There was an aroma of aftershave, and a damp towel lay over the only chair in the room apart from the one occupied by Sand himself. She could see his hair was wet.

He picked up the towel, threw it into a corner, and invited her to sit down. The chair was damp. She sat anyway.

Håkon Sand and Karen Borg were old friends who never saw each other. They always exchanged the customary pleasantries, like How are you, it’s been a long time, we must have dinner one day. A regular routine whenever they happened to meet, in the street or at the homes of mutual friends who were better at keeping in touch.

“I’m glad you came. Very pleased, in fact,” he said suddenly. It didn’t look like it. His smile of welcome was strained and tired after twenty-four hours on duty.

“The guy’s refusing to say anything at all. He just keeps repeating that he wants you as his lawyer.”

Karen Borg lit a cigarette. She defied all the warnings and smoked Prince Originals. The “Now I’m smoking Prince too” type, with maximum tar and nicotine and a frightening scarlet warning label from the Department of Health. No one cadged a smoke from Karen Borg.

“It ought to be easy enough to make him see that’s impossible. For one thing, I’m a witness in the case, since I was the one who found the body, and second, I’m not proficient in criminal law. I haven’t handled criminal cases since my exams. And that was seven years ago.”

“Eight,” he corrected her. “It’s eight years since we took our exams. You came third in our year, out of a hundred and fourteen candidates. I was fifth from the bottom. Of course you’re proficient in criminal law if you want to be.”

He was annoyed, and it was contagious. She was suddenly aware of the atmosphere that used to come between them when they were students. Her consistently glowing results were in stark contrast to his own stumbling progress towards the final degree exam that he would never even have scraped a pass in without her. She had pushed and coaxed and threatened him through it all, as if her own success would be easier to bear with this burden on her shoulders. For some reason which they could never fathom, perhaps because they’d never talked about it, they both felt she was the one who had the debt of gratitude to him, and not the other way round. It had irritated her ever since, this feeling of owing him something. Why they had been so inseparable throughout their student years was something nobody understood. They had never been lovers, never so much as a little necking when drunk, but a mismatched pair of friends, quarrelsome yet bound by a mutual concern that gave them an invulnerability to many of the vicissitudes of student life.

“And as for you being a witness, I don’t give a shit about that right now. What’s more important is to get the man to start talking. It’s obvious he won’t cooperate until he gets you as his defence counsel. We can think again about the witness stuff when we have to. That’ll be a good while yet.”

“The witness stuff.” His legal terminology had never been particularly precise, but even so Karen Borg found this grated on her. Håkon Sand was a police attorney, and his job was to uphold the law. Karen Borg wanted to go on believing the police took the law seriously.

“Can’t you talk to him anyway?”

“On one condition. You give me a credible explanation of how he knows who I am.”

“That was actually my fault.”

Håkon smiled with the same feeling of relief he’d had whenever she’d explained something he’d read ten times before without comprehending. He fetched two cups of coffee from the anteroom.

Then he told her the story of the young Dutch national whose only contact with working life—according to reports so far—had been drug trafficking in Europe. How this Dutchman, now sitting as tight-lipped as a clam waiting for Karen Borg in one of the toughest billets in Norway, the custody cells in Oslo police headquarters, knew exactly who Karen Borg was—a thirty-five-year-old very successful commercial lawyer totally unknown to the general public.

“Bravo Two-Zero calling Zero-One!”

“Zero-One to Bravo Two-Zero, go ahead.”

The police officer spoke in hushed tones, as if he were expecting a confidential secret. Far from it. He was on duty in the operations room. It was a large open space with a shelved floor in which raised voices were taboo, decisiveness a virtue, and economy of expression vital. The duty shift of uniformed officers sat perched above the theatre floor, with an enormous map on the opposite wall to chart the scene of the main action, the city of Oslo itself. The room was as centrally positioned in the police headquarters building as it could be, with not a single window looking out onto the restless Saturday evening. The city night made its presence felt in other ways: by radio contact with the patrol cars and a supportive 002 number for the assistance of the public of Oslo in their moments of greater or lesser need.

“There’s a man sitting in the road on Bogstadsveien. We can’t get anything out of him, his clothes are covered in blood, but he doesn’t look injured. No ID. He’s not putting up any resistance, but he’s obstructing the traffic. We’re bringing him in.”

“Okay, Bravo Two-Zero. Report when you’re back on patrol. Received Zero-One. Over and out.”

Half an hour later the suspect was standing at the reception desk. His clothes were certainly bloody: Bravo Two-Zero had been right about that. A young rookie was searching him. With his unmarked blue epaulettes lacking even a single stripe as insurance against all the vilest jobs, he was terrified of so much possibly HIV-infected blood. Protected by rubber gloves, he pulled the open leather jacket off the arrested man. Only then did he see that his T-shirt had originally been white. His denim jeans were covered in blood too, and he had a general air of self-neglect.

“Name and address,” said the duty officer, glancing up wearily over the counter.

The suspect didn’t reply. He just stared longingly at the packet of cigarettes the young officer was shoving into a brown paper bag together with a gold ring and a bunch of keys tied with a nylon cord. The desire for a smoke was the only sign that could be read in his face, and even that disappeared when his eyes shifted away from the paper bag to the duty officer. He was standing nearly a metre away from the policeman, behind a strong metal barrier that came up to his hips. The barrier was shaped like a horseshoe, with both ends fixed into the concrete floor, half a metre from the high wooden counter, quite wide in itself, over which projected the nose and thinning grey hair of the police officer.

“Personal details, please! Name! Date of birth?”

The anonymous man smiled, but not in the least derisively. It was more an expression of gentle sympathy with the exhausted policeman, as if he wanted to indicate that it was nothing personal. He had no intention of saying anything at all, so why not just put him in a cell and have done with it? The smile was almost friendly, and he held it unwaveringly, in silence. The duty officer misunderstood. Needless to say.

“Put the bugger in a cell. Number four’s empty. I’ve had enough of his insolent attitude.”

The man made no protest, but went along willingly to cell number four. There were pairs of shoes in the corridor outside every cell. Well-worn shoes of all sizes, like door nameplates announcing the occupants. He must have automatically assumed the regulation would also apply to him, because he kicked off his trainers and stood them neatly outside the door without being asked.

The cell was about three metres by two, bleak and dreary. Floor and walls were a dull yellow, with a noticeable absence of graffiti. The only slight advantage he was immediately aware of in these surroundings, so far remo

ved from the comforts of a hotel, was that his hosts were obviously not sparing with the electricity. The light was dazzling, and the temperature in the little room must have been at least twenty-five degrees Celsius.

Just inside the door there was a sort of latrine; it could hardly be called a lavatory. It was a construction of low walls with a hole in the middle. The moment he saw it, he felt his bowels knotting up in constipation.

The lack of any inscriptions on the walls by previous guests didn’t mean there were no traces of frequent habitation. Even though he was far from freshly showered himself, he felt quite queasy when the unpleasant odour hit him. A mixture of piss and excrement, sweat and anxiety, fear and anger: it permeated the walls, evidently impossible to eradicate. Because apart from the structure designed to receive urine and faeces, which was beyond all hope of cleansing, the room was actually clean. It was probably swilled out every day.

He heard the bolt slam in the door behind him. Through the bars he could hear the man in the next cell continuing where the duty officer had given up.

“Hey, you, I’m Robert. What’s your name? Why’ve the pigs got you?”

Robert had no luck either. Eventually he had to admit defeat too, just as frustrated as the duty officer.

“Bastard,” he muttered after several minutes of trying, loud enough for the message to get through to its intended recipient.

There was a platform built into the end of the room. With a certain amount of goodwill it might perhaps be described as a bed. There was no mattress, and no blanket lying around anywhere. Well, that was okay, he was already sweating profusely in the heat. The nameless man folded up his leather jacket to make a pillow, lay with his bloody side downwards, and went to sleep.

When Police Attorney Håkon Sand came on duty at five past ten on Sunday morning, the unknown prisoner was still asleep. Håkon didn’t know that. He had a hangover, which he shouldn’t have had. Feelings of remorse were making his uniform shirt stick to his body. He was already running his finger under his collar as he came through the CID area towards the police lawyers’ office. Uniforms were crap. At the beginning, all the legal specialists in the prosecution service were fascinated by them—they would stand in front of the mirror at home admiring themselves, stroking the insignia of rank on the epaulettes: one stripe, one crown, and one star for inspector, a star that might become two or even three depending on whether you stuck it out long enough to become a chief inspector or superintendent. They would smile at the mirror, straighten their shoulders involuntarily, note that their hair needed cutting, and feel clean and tidy. But after an hour or two at work they would realise that the acrylic made them smell and their shirt collars were much too stiff and made sore red weals round their necks.

A Grave for Two

A Grave for Two Dead Joker

Dead Joker Death of the Demon: A Hanne Wilhelmsen Novel

Death of the Demon: A Hanne Wilhelmsen Novel Punishment aka What Is Mine

Punishment aka What Is Mine Beyond the Truth

Beyond the Truth Death in Oslo

Death in Oslo The Blind Goddess

The Blind Goddess What Never Happens

What Never Happens 1222

1222 In Dust and Ashes

In Dust and Ashes Odd Numbers

Odd Numbers What is Mine

What is Mine What Dark Clouds Hide

What Dark Clouds Hide Blessed Are Those Who Thirst

Blessed Are Those Who Thirst Fear Not

Fear Not No Echo

No Echo Hanne Wilhelmsen - 01 - The Blind Goddess

Hanne Wilhelmsen - 01 - The Blind Goddess