Death in Oslo Read online

Page 2

‘You look lovely, by the way!’

The woman smiled faintly, almost embarrassed.

‘See you again soon,’ she said and rolled over to the window, where she remained sitting with her back to her guest, without saying goodbye.

IV

The snow lay knee-deep over the long strips of field. It had been frosty for a long time now. The naked trees in the woods to the west were glazed with ice. Every now and then his snowshoes broke through the rough crust on the snow, making him nearly lose his balance for a moment. Al Muffet stopped and caught his breath. The sun was about to go down behind the hills to the west. Only the odd bird cry broke the silence. The snow glittered in the golden-red evening light and the man with the snowshoes stood for a moment to watch a hare that leapt out from the woods and zigzagged down to the stream on the other side of the field.

Al Muffet breathed in as deeply as he could.

He had never doubted that he had done the right thing. When his wife died and he was left with three daughters aged eight, eleven and sixteen, it took only a matter of weeks for him to realise that his career at one of Chicago’s prestigious universities was simply not compatible with sole responsibility for his children. Their finances also implied that he should move what was left of his family to a quiet place in the country as soon as possible.

Three weeks and two days after the family had moved to their new home at Rural Route #4 in Farmington, Maine, two passenger planes each flew into a tower on Manhattan. A few minutes later, another thundered into the Pentagon. That same evening, Al Muffet closed his eyes in silent gratitude for his foresight: already, as a student, he had shed his real name, Ali Shaeed Muffasa. The children were sensibly called Sheryl, Catherine and Louise, and had all inherited their mother’s delightful snub nose and ash-blonde hair.

Now, a good three years later, barely a day passed without him enjoying his country life. The girls were blossoming, and he had rediscovered the joys of clinical practice remarkably quickly. His practice was varied, a good mixture of small animals, pets and farm animals: poorly canaries, dogs giving birth, and every now and then an aggressive ox that needed a bullet through the head. Every Thursday he played chess down at the club. He went to the cinema with the girls on Saturdays. On Monday evenings he generally played a couple of games of squash with a neighbour who had a court in a converted barn. One day followed the next, a steady flow of pleasing monotony.

Only on Sundays were the Muffets any different from the rest of the community. They did not go to church. Al Muffet had lost any contact with Allah a long time ago, but had no plans of getting to know God. Initially, there was some reaction: veiled questions at parents’ meetings, ambiguous remarks at the petrol station or by the popcorn machine at the cinema on a Saturday night.

But these gradually petered out.

Everything passes, Al Muffet thought to himself as he struggled to unearth his watch, which was buried under his mitten and his down jacket. He had to get a move on. His youngest daughter was going to make dinner, and from experience, he knew that it was worthwhile being at home when she did. Unless he wanted to be greeted by an extravagant meal and a bare goodies store. The last time Louise had made dinner it had been a Monday night and she had served up a four-course meal of foie gras, truffle risotto, and the venison he had got in the autumn and intended to have for their annual Christmas dinner with the neighbours.

The cold had more bite now that the sun had gone down. He took off his mittens and put his palms to his cheeks. A few seconds later he started to walk, with the long, slow snowshoe steps that he had finally mastered.

He had not watched the swearing-in of the President, but not because it would bother him in any way. When Helen Lardahl Bentley had entered the public arena, big time, ten years ago, he had in fact been horrified. He remembered with unnerving clarity that morning in Chicago, when he was lying at home in bed with flu, channel-hopping through his fever. Helen Lardahl, so different from how he remembered her, making a speech in the Senate. Gone were the glasses. The puppy fat that had stayed with her far into her twenties had fallen away. Only characteristics such as the determined diagonal movement through the air with an open, flat hand to underline every second point convinced him that it really was the same woman.

How does she dare? he’d thought at the time.

And then he had gradually come to accept it.

Al Muffet stopped again and drew the ice-cold air into his lungs. He was down by the stream now, where the water was still running under a lid of clear ice.

She trusted him, it was simple. She must have chosen to trust the promise he had made back then, a lifetime ago, in another life and in a completely different place. Given her position, it would have been simple to find out whether he was still alive, still lived in the US.

But now she had got herself elected as the world’s most powerful national leader, in a country where morality was a virtue and double standards a necessity.

He stepped across the stream and scrambled over the mounds of snow left by the snowplough. Suddenly his pulse was so fast that his ears were ringing. It was so long ago, he thought, and took off his snowshoes. With one in each hand, he started to run down the small, wintry road.

‘We got away with it,’ he whispered in rhythm with his own heavy steps. ‘I am to be trusted. I am a man of honour. We got away with it.’

He was far too late. No doubt he would get home to oysters and an open bottle of champagne. Louise would say it was a celebration, in honour of the first female president of America.

MONDAY 16 MAY 2005

I

‘Bloody great timing. Who the hell chose that date?’

The Director General of the Norwegian Police Security Service, PST, brushed a hand over his cropped ginger hair. ‘You know perfectly well,’ replied a slightly younger woman, who was watching an old TV screen that was balanced on a filing cabinet in the corner of the office. The colours were faded and a black stripe flickered at the bottom of the image. ‘It was the Prime Minister. Great opportunity, you know, to show the old country in all its national romantic glory.’

‘Drunkenness, trouble and rubbish everywhere,’ grunted Peter Salhus. ‘Not very romantic. Our national day has become pure hell. And how in God’s name’ – he was shouting now as he pointed at the TV – ‘do they think it will be possible to look after that woman?’

Madam President was about to set foot on Norwegian soil. In front of her were three men in dark overcoats. The characteristic earpieces were clearly visible. Despite the low cloud, they were all wearing sunglasses, as if they were trying to parody themselves. Their doubles were coming down the steps from Air Force One behind the President; just as big, just as brooding and just as devoid of expression.

‘Looks like they could do the job on their own,’ Anna Birke-land quipped, nodding at the screen. ‘And I hope that no one else shares your . . . pessimism, shall we say. I’m actually quite worried. You don’t normally . . .’

She broke off. Peter Salhus didn’t say anything either, his eyes fixed on the TV screen. It was not like him to have such an outburst. Quite the contrary: when, a couple of years previously, he was appointed as director general, a post that historically had some embarrassing blemishes, it was because of his placid and pleasant nature, and not because of his military background. The protests from the left had been muted by the revelation that Salhus had been a young socialist. He had joined the army at nineteen in order to ‘expose American imperialism’, he explained with a smile in an interview broadcast on TV. When he then gave an earnest one-anda-half-minute account of the threats facing modern society, which most people could recognise, the battle was as good as won. Peter Salhus had changed out of his uniform and into a suit, and moved into the PST offices, if not with universal acclaim, then at least with cross-party support behind him. He was well liked by his staff and respected by his colleagues abroad. His cropped military hair and salt-and-pepper beard gave him an air of old-fashion

ed, masculine confidence. Paradoxically, he was in fact a popular head of security.

And Anna Birkeland had never seen this side of him.

The light in the ceiling was reflected in the sweat on his brow. He rocked his body backwards and forwards, apparently without realising. When Anna Birkeland looked at his hands, they were clenched tight.

‘What is it?’ she asked in such a quiet voice that it almost seemed she didn’t want an answer.

‘This was not a good idea.’

‘Why haven’t you stopped it, then? If you’re as worried as you seem to be, you should have—’

‘I’ve tried. And you know it.’

Anna Birkeland got up and walked over to the window. Spring was not springing in the pale grey afternoon light. She put her palm up to the glass. An outline of condensation flared up briefly, then disappeared.

‘You had your objections, Peter. You outlined possible scenarios and pointed out possible problems. But that’s not the same as trying to stop something.’

‘We live in a democracy,’ he said. As far as Anna could make out, there was no irony in his voice. ‘It is the politicians who decide. In situations like this, I’m merely an adviser. If I could decide—’

‘Then we would keep everyone out?’ She turned suddenly. ‘Everyone,’ she repeated, louder this time. ‘Everyone who might in any way threaten this idyllic village called Norway.’

‘Yes,’ he replied. ‘Perhaps.’

His smile was difficult to interpret. On the TV screen, the President was being led from the enormous jet towards a temporary lectern. A man dressed in a dark suit fiddled with the microphone.

‘Everything went well when Bill Clinton came,’ Anna said and carefully bit her nail. ‘He went walkabout in town, drank beer, and greeted every man and his dog. Even went for cake. Without it being planned and agreed in advance.’

‘Yes, but that was before.’

‘Before what?’

‘Before nine/eleven.’

Anna sat down again. She ran her hands up her neck and lifted her shoulder-length hair. Then she looked down and took a breath as if about to say something, but instead released an audible sigh. The President had already finished her short speech on the silent TV.

‘Oslo Police is responsible for the bodyguards now,’ she said finally. ‘So, strictly speaking, the President’s visit is not your concern. Ours, I mean. And in any case . . .’ she waved a hand at the filing cabinet under the TV, ‘we’ve found nothing. No movement, no activity. Not among any of the groups we’re aware of here. Not even on the peripheries. We’ve received nothing from elsewhere to indicate that this will be anything other than a friendly visit from . . .’ her voice took on the intonation of a newsreader, ‘a president who wishes to honour her homeland and the USA’s great ally, Norway. There is nothing to indicate that anyone has other plans.’

‘Which is strange, isn’t it? This is . . .’

He held back. Madam President got into a dark limousine. A woman with lightning hands helped her with her coat. It was hanging out of the car and about to be caught by the door. The Norwegian prime minister smiled and waved at the cameras, a bit too vigorously, with childish delight at having such an important visitor.

‘There goes the world’s most hated person,’ Peter finished and nodded at the screen. ‘I know that plots are hatched to assassinate the woman every day. Every bloody day. In the States, in Europe. In the Middle East. Everywhere.’

Anna Birkeland sniffed, and wiped the tip of her nose with her finger.

‘But that’s always been the case, Peter. And she’s not the only one that people want to assassinate. All over the world intelligence services are constantly uncovering irregularities so that they don’t become realities. And America has got the world’s best intelligence service, so—’

‘People in the know might dispute that,’ he interrupted.

‘And the world’s most efficient police organisation,’ she continued, unaffected. ‘I don’t think you need lose any sleep worrying about the President of the United States of America.’

Peter Salhus got up and pressed the off button with his great index finger, just as the camera zoomed in for a close-up of the small American flag attached to the side of the bonnet. It was whipped into a frenzy of red, white and blue as the car accelerated.

The screen went black.

‘It’s not her I’m worried about,’ Peter Salhus said. ‘Not really.’

‘Now I really don’t know what you’re talking about,’ Anna exclaimed, with obvious impatience. ‘I’m off. You know where to find me if you need me.’

She picked up a voluminous folder from the floor, straightened her back and walked to the door. She had half opened it when she turned and asked, ‘If it’s not Bentley you’re worried about, who is it?’

‘Us,’ he replied, sharp and concise. ‘I’m worried about what might happen to us.’

The door handle felt strangely cold against her palm. She took her hand away. The door slowly closed again.

‘Not the two of us.’ He smiled at the window; he knew she was blushing, and didn’t want to look. ‘I’m worried about . . .’ He drew a big, vague circle of nothing with his hands. ‘Norway,’ he finished, and finally looked her in the eye. ‘What the hell will happen to Norway if something goes wrong?’

She wasn’t sure that she understood what he meant.

II

Madam President was finally alone. She had a headache clinging to the bottom of her skull, as she always did at the end of a day like today. She sat down carefully in one of the cream armchairs. The headache was an old friend, a frequent visitor. Medicine didn’t help, probably because she had never disclosed this problem to a doctor and therefore had never used anything other than over-the-counter painkillers. Her headache came at night, when everything was done and she could finally kick off her shoes and put her feet up. Read a book, or maybe close her eyes and think about nothing before falling asleep. But she couldn’t. She had to sit still, leaning back, with her arms out from her body and her feet firmly on the ground. Her eyes half closed, never fully; the red darkness behind closed eyes just made the pain worse. She needed a bit of light. A sliver of light between her lashes. Loose arms with open hands. Relaxed torso. She had to shift her attention as far away from her head as possible, to her feet, which she pressed as hard as she could into the carpet. Again and again, to the beat of her pulse. Don’t think. Don’t close your eyes. Press your feet down. And again, and again.

Eventually, in a delicate balance between sleep, pain and wakefulness, the claws at the back of her head slowly loosened their grip. She never knew how long an attack would last. Generally it was about a quarter of an hour, though sometimes she stared in horror at her watch and could not believe that that was the time. Occasionally, it was only a matter of seconds.

As was the case this time, she realised when she looked at the alarm clock.

She tentatively lifted her right hand and wrapped it round her neck. She continued to sit absolutely still. Her feet were still pulsing against the floor, heel to toe and back again. The cool of her palm made the skin contract across her shoulders. The pain had really vanished, completely. She let out a sigh of relief and got up as slowly as she had sat down.

The worst thing about the attacks was perhaps not so much the pain as the fact that she felt so awake afterwards. Over the past twenty years or so, Helen Bentley had learnt to accept that sleep was something she sometimes just had to do without. She could go for months on end with no pain, but the armchair scenario had almost become a midnight ritual for her over the past year. And as she was a woman who never let anything go to waste, not even time, she constantly surprised her colleagues by how well prepared she was for early-morning meetings.

The US had, unwittingly, elected a president who normally had to make do with only four hours’ sleep. And if it was up to her, her insomnia would remain a secret that she shared only with her husband, who had learnt after many

years to sleep with the light on.

But now she was alone.

Neither Christopher nor her daughter, Billie, was with her on this trip. Madam President had gone to great pains to stop them. She still cringed when she remembered the astonished disappointment in her husband’s eyes when she made the decision to travel alone. The trip to Norway was the President’s first official visit abroad after having been sworn in, and it was of a purely representative nature. Not only that, it also was to a country that her twenty-one-year-old daughter would have had great pleasure and interest in visiting. There were a thousand and one good reasons why the family should go, as originally planned.

But she had made them stay at home, all the same.

Helen Bentley took a few cautious steps, as if she was afraid that the floor wouldn’t hold. Her headache had definitely disappeared. She rubbed her forehead with her thumb and index finger as she looked around the room. It was the first time she had really noticed how beautifully the suite was designed. It was done out in cool Scandinavian style, with blond wood, light materials and perhaps a little too much glass and steel. The lights in particular caught her attention. The lamp bowls were made of sand-blasted glass. Though they were not all the same shape, they harmonised with each other in a way that meant that they somehow belonged together without her understanding why. She ran her hand over one of them. A delicate warmth seeped through from the low-wattage bulb.

They’re everywhere, she thought to herself and stroked her fingers over the glass. They’re everywhere, and they’ll look after me.

A Grave for Two

A Grave for Two Dead Joker

Dead Joker Death of the Demon: A Hanne Wilhelmsen Novel

Death of the Demon: A Hanne Wilhelmsen Novel Punishment aka What Is Mine

Punishment aka What Is Mine Beyond the Truth

Beyond the Truth Death in Oslo

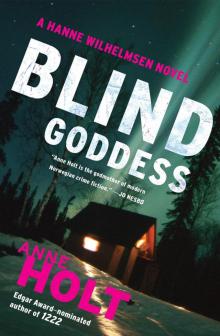

Death in Oslo The Blind Goddess

The Blind Goddess What Never Happens

What Never Happens 1222

1222 In Dust and Ashes

In Dust and Ashes Odd Numbers

Odd Numbers What is Mine

What is Mine What Dark Clouds Hide

What Dark Clouds Hide Blessed Are Those Who Thirst

Blessed Are Those Who Thirst Fear Not

Fear Not No Echo

No Echo Hanne Wilhelmsen - 01 - The Blind Goddess

Hanne Wilhelmsen - 01 - The Blind Goddess